What should we know about Ebola?

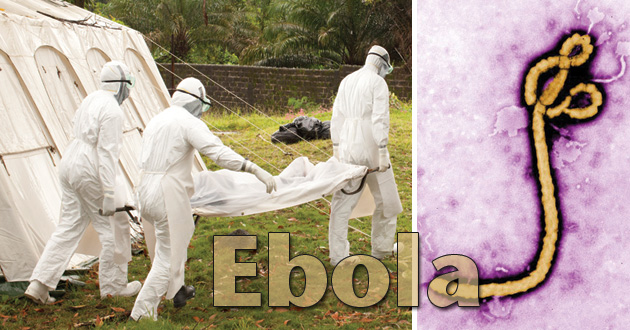

The Ebola epidemic has stricken West Africa and is the largest epidemic in history with more than 13,000 cases and 4,900 deaths in the past six months.

The World Health Organization reported on Oct. 14 that the number of new Ebola cases could reach 10,000 per week by December.

Two imported cases, including one death, and two locally acquired cases in healthcare workers have been reported in the United States. CDC and partners are taking precautions to prevent the further spread of Ebola within the United States.

U.S. national airport hubs have begun implementing procedures to screen travelers while questions are being raised as to the potential miss-diagnosis of the first U.S. fatality from Ebola. To address the global spread, the U.S. State Department is soliciting more countries to help in the fight and some European leaders are stepping up to assist.

There are still some lingering questions as to the precise screening protocols being used by government agencies for any and all of those persons who have re-entered the county from the affected African region over the past several weeks.

Here is a list of questions and answers on Ebola from the Christian Emergency Network.

Dr. Kent Brantly talks about surviving Ebola and how he believes he contracted the virus

Questions and Answers on Ebola

What is Ebola?

Peter Piot discovered Ebola in 1976. He named it after a river in the Congo. He currently believes the Ebola virus may be about to become catastrophic. After much study with U.S. Army medical researchers, Richard Preston, the author of The Hot Zone, defined the term Ebola this way: “The Ebola virus is a member of a family of viruses called hemorrhagic fever viruses, another one being the “Marburg Virus”. Viruses inhabit a place between inanimate material and living things. There is dispute among experts as to whether they are living or dead. Certainly, they act “dead” when outside of cells. All living things are infected by viruses, even bacteria, mold, fungi, plants and animals.”

Many viruses are harmless, but many can cause disease. A virus is a chain of DNA or RNA encased in a protein coat. The virus particles have an area on the protein coat which can connect with the cell membrane. Some viruses bore a hole through the cell membrane (or cell wall) and inject the genetic DNA or RNA into the cell. Others induce the cell to take them in. When the particles have entered, they take over the cell’s metabolic factory, and force the cell to make many virus particles. This process exhausts the cell and kills it. Then, the cell breaks open and hundreds of virus particles spill out. Thus, a virus cannot replicate itself without the help of the cell’s “manufacturing factory”.

The Ebola virus attacks the immune and clotting systems most vigorously, causing the infected individual to bleed to death. There are a few different strains of the virus, the most virulent, according to Richard Preston, is the Mayinga strain, which appeared in October 1976 in Zaire. This strain had a fatality rate of 90%. Fortunately, relatively speaking, the current viral strain has a fatality rate of “only” 50%.

What are the symptoms of Ebola?

At first, the Ebola virus reacts like many other viral infections. The first symptoms may include a rash similar to measles, fever, headache, joint and muscle aches, sore throat, weakness, diarrhea, vomiting, and stomach pain. The disease may progress to internal and external bleeding.

The virus is said to be transmissible only when the affected person is symptomatic. That is reported to vary between 8 days and three weeks. Thus, a person who is infected but not symptomatic could board a plane and not be infectious until he/she arrived in the U.S.

Where did Ebola come from?

In the past, Ebola virus outbreaks were confined to small areas of tropical Africa, were sporadic, and sickened 30-50 people, then disappeared for several years between outbreaks. From recent reports, many more people have died from this current outbreak than in all the previous known outbreaks. Why is this? Where the virus comes from and where it goes, nobody knows. What we do know is many viruses have a reservoir, such as rabies in bats. The rabies-based bat virus does not kill all bats, yet may be transmitted to other animals by a bat bite. It has not been shown thus far, what, if any, reservoir the Ebola virus hides in. As of 1993, rats, bats, monkeys, mosquitoes, and mice all have not been proven to harbor the virus.

How does the Ebola virus spread?

Most people know that cold viruses generally spread from person to person by fine water droplets emitted by people sneezing. Viruses are also transmitted by hand-to-hand contact. A less pleasant, but no less important means of spread is by what is termed the fecal-oral route, typical of polioviruses. Frequent hand washing can minimize the spread of polioviruses.

As for the Ebola virus (and other Hemorrhagic Fever viruses) it has long been thought that the virus is transmitted by contact with the affected person’s “body fluids”. According to Richard Preston: “These fluids were thought to be blood, stomach contents, semen, saliva and diarrhea”. Although, It has not been thought to be transmissible by coughing or sneezing, if cases are discovered which have an air borne transmission component the spread is likely to advance rather quickly. This variable could be a “game changer” in terms of making a personal decision to self-quarantine.

A well-established procedure for curtailing the Ebola virus has been to isolate the infected and closely monitor those who have come into contact with them. Unfortunately, many of the countries in which the Ebola has spread were those who have experienced civil unrest without medical treatment capacities and systems were stable when the outbreak first occurred. Many of the doctors have themselves died of the Ebola in Liberia, for example. People in these highly populated African countries are often nomadic making tracing their contacts problematic at best, impossible at worst.

What is different about this Ebola strain?

However, something seems to be different with this outbreak. Some have suggested that it is our increased ability to travel. Certainly, it would seem that the local outbreaks seen in the 1970s and 1980s might be explained by the fact that many African people were unable to travel. This raises the possibility that the virus has mutated and is thus being transmitted in a different fashion. Certainly, we know that flu viruses are capable of changing their genetic makeup, as is the AIDS virus, thus eluding attempts to destroy them.

Time may work against really virulent viruses. Those that rapidly kill or significantly injure their host, like the Ebola virus, have less opportunity to spread. Most viruses devolve to less virulence and with more symptoms to induce spread through cough, sneezing, lots of secretions like runny nose, or diarrhea. Less severe viral disease allows the host to continue exposing others.

Do we know the full story on Ebola?

Getting an understanding of actual risk takes time. The Centers for Disease Control may be endeavoring to avoid jumping to conclusions or intent on preserving their integrity and avoiding panic; or they may be reluctant to share information that may prove inconclusive. Regardless of their motives, they need to be accurate to avoid public loss of confidence, which would be the crisis within the crisis. Since the CDC is totally data driven, the public may or may not understand it takes time to collect and analyze a vast amount of data. However, while the CDC and other federal public health agencies have have issued public awareness materials and fielded questions, more questions have arisen versus answers. Still, cases like Thomas Duncan in Dallas, Texas remain troubling. In his case, the doctors, at the hospital saw him and sent him home, even though he said that he had been to Liberia, had close contact with his family, and had actually thrown up in the parking lot upon his return. Compounding his circumstances, the ambulance people who took him back to the hospital and the people who cleaned up his vomit in the parking lot did not wear protective clothing, according to open source news reports. This leaves us wondering what stringent measure will be put in place, by whom, and when? What are the steps that need to be taken to get better control of this outbreak? If it is as we are told that the Ebola virus is not as worrisome as the MERS or Avian flu outbreak, what are the unknowns we are facing? Who is managing the objectives of this outbreak being controlled? Is it the World Health Organization or the Centers for Disease Control? And, are they devoid of political and economic ideology? What is a responsible balanced timeline for robust control?

What about Ebola vaccines?

From what we have gathered from CEN experts in the field, there are several reasons why there is currently not a vaccine, or enough vaccine to curb the spread of Ebola. Generally, the CDC appears to be putting out good information, however, they seem to be delayed by their extensive reporting, analyzing, validation and verification process. Our CEN subject experts believe the CDC is working to provide trust worthy information, however, there may be wide gaps in government policies which reflect the information being provided. Budget cuts to many research agencies as well as a realignment of priorities in recent years with a greater focus upon biodefense has been a contributor. And, there is a lengthy time to get a vaccine approved by the Federal Drug Administration in addition to reluctance on the part of the private sector to develop and market treatments in which the demand may be uncertain.

What does this mean for us?

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and President Obama, there is “little chance that Ebola will spread to the U.S.”, yet it appeared a few days later in Dallas, Texas raising the concern this virus may not be completely understood or accurately depicted to the public. How do you make personal choices on self-care with conflicting information? And, if Ebola is being transmitted from Africa, is it not reasonable to suggest U.S. authorities may begin restricting people from coming to America from Africa now rather than after they have exhausted the 23 bed limitation that exists now to deal with such cases in the U.S.? If officials are too late in issuing restrictions, what does this mean about making travel choices? If, a 21-day self-quarantine becomes mandatory given any exposure to Ebola, what are the challenges we would face as a family or nation if we needed to do this for three weeks or more to constrain the spread? Do we need to know basic caregiving tactics for home care if our domestic facilities become over crowded or if we need to self-quarantine with or without notice? We don’t know the answers to these questions, but God does!

If you travel to an area affected by Ebola what precautions should you take?

- Wash hands frequently or use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer.

- Avoid contact with blood and body fluids of any person, particularly someone who is sick.

- Do not handle items that may have come in contact with an infected person’s blood or body fluids.

- Do not touch the body of someone who has died from Ebola.

- Do not touch bats and nonhuman primates or their blood and fluids and do not touch or eat raw meat prepared from these animals.

- Avoid facilities in West Africa where Ebola patients are being treated. The U.S. Embassy or consulate is often able to provide advice on medical facilities.

- Seek medical care immediately if you develop fever, headache, muscle pain, diarrhea, vomiting, stomach pain, or unexplained bruising or bleeding.

- Limit your contact with other people until and when you go to the doctor. Do not travel anywhere else besides a healthcare facility.

— Compiled by Mary Marr, CEN National Founder and President. Reprinted with permission.

References:

Ebola updates from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention

Marr, Mary “Should the Church Fear Ebola” (Part I), CEN National Founder and President

Preston, Richard “The Hot Zone” published in 1994 by Random House (based upon information by U.S. Army Medical officials)

Sangster, Paul MD, CEN National Medical Advisor — http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/Pages/home.aspx