Family and forgiveness: A dazzling cast and timeless values propel Black Nativity

If you’ve ever been to a black Baptist church, you know you’re in for a cascade of full-body, full-spirit praise and dance. Now imagine that performed as a Christmas musical drama—a mishmash of classic Christmas hymns, soul-stirring gospel, and contemporary rap—and you’ve got the film Black Nativity.

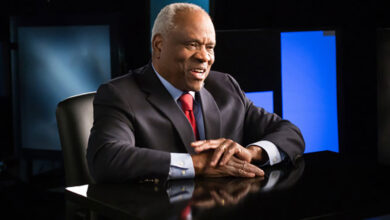

Black Nativity (rated PG for thematic material, language, and a menacing situation) is adapted from Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes’ most celebrated play, an all-black cast remake of the nativity story. The play was first performed Off-Broadway in 1961 and still appears in various theaters across the nation. The on-screen version hopes to appeal to the mainstream public with the addition of a high-caliber cast that includes award-winning actors Forest Whitaker (The Last King of Scotland) and Jennifer Hudson (Dreamgirls).

Like the play, writer/director Kasi Lemmons swaths old-time carols with hand-swaying, foot-stomping enthusiasm, brilliant colors, and Afrocentric percussion. That nativity scene plays out in a dream sequence, but the main story is about meeting the grandparents.

Teenager Langston (played by precocious 17-year-old Jacob Latimore) travels from Baltimore to Manhattan on a Peter Pan bus, with little more than a heavy parka and a backpack. He and his single mother, Naima (Jennifer Hudson), are being evicted, so his mother sends him to her estranged parents in Harlem for Christmas.

Standing pie-eyed among flashing billboards, glinting skyscrapers, and pushing crowds, Langston has never felt lonelier. He doesn’t understand his prim-and-proper grandparents, Rev. Cornell and Aretha Cobbs (Whitaker and Angela Bassett), and they don’t understand him. His grandfather, all dapper in a plaid coat, black vest, and pocket watch, criticizes his low-riding jeans during grace at dinner. His grandmother, elegant and handsome in a rich-textured sweater and pearls, embraces and studies him with sad eyes, but is otherwise a nervous hummingbird, flitting around trying to soothe tensions between grandpa and grandson.

Don’t watch Black Nativity for the thrill or suspense: Despite some story “twists,” the plot is as predictable as the story of Baby Jesus. No, watch it for the dazzling scale of talents: Hudson’s clear-waterfall vocals dueting with Bassett’s silky baritone to “He Loves Me Still.” Grammy-winning Mary J. Blige in a snowy Afro, belting out a new rendition of “Rise Up Shepherd and Follow” with rapper Nas. And Latimore—boy, can that teen trill a heartache.

One of the major themes in Black Nativity—forgiveness and redemption—is central to the least likely character of the movie: the Reverend. Stern and sorrowful at home, Rev. Cornell transforms into an exuberant preacher of God’s forgiveness on the pulpit—but then in front of his congregation he reveals his past mistake and begs his daughter’s forgiveness. It’s a powerful, joyful, yet tear-jerking scene.

Executive producer Bishop T.D. Jakes, who edited the script to reach “a wider faith-based audience,” said he wanted Rev. Cornell to be “believable as a human, without being disrespectful.” It’s a side of the clergy not often revealed in Hollywood—and Whitaker nails it, humanizing the church leader with sympathetic rawness.

Whitaker said he drew inspiration for his character from his own upbringing as a Baptist preacher’s grandson and a church elder’s son. He also watched sermons of famous preachers online, read the Scriptures, and tried to channel the charisma of Martin Luther King Jr. “The big challenge was how to embody the character of a preacher in an honest way,” Whitaker said. “It’s a high-scrutiny job. A pastor is an important model in the church and community but that doesn’t always translate into all areas in his personal life.”

Like any other feel-good holiday movie, Black Nativity highlights timeless, universal values that reflect across all races, cities, and religions: family and forgiveness. As for the message to a faith-focused audience, Bassett said, “It’s about knowing that you’re imperfect, but that God still extends his grace and brings fellowship to you.”

— by Sophie Lee