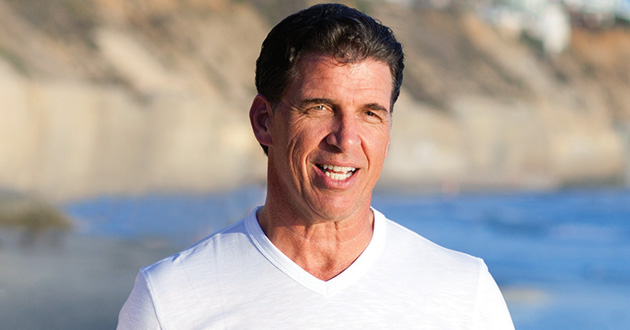

Tackling fatherhood | Former Chargers linebacker extols role of Mr. Mom

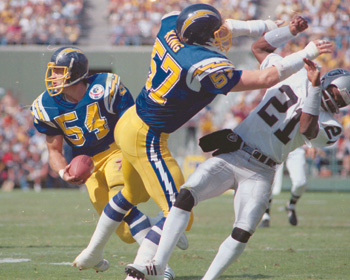

Billy Ray Smith Jr. was a second-grader playing Pee Wee football when his dad—already a successful NFL defensive lineman for the Baltimore Colts—taught him a transformational lesson from the bleachers.

“A guy knocks me down and as I was trying to get back up, he pushed me down again,” said the junior Smith, who went on to make his own name as a linebacker and defensive captain with the San Diego Chargers. “I could hear my dad, over everybody else in the crowd, laughing. He’s not laughing at me, He’s just laughing because he thinks its funny that I think I’m a real (tough) football player and yet they’re knocking me down. They’re pushing me around. I could hear him laughing and, boy, I tell you it just flipped a switch. It was something else.”

The memory unleashes within Smith a deep laugh, one with a ringing quality likely reminiscent of the head rattle he dished out upon his on-field victims.

The episode taught the young Smith the value in not taking yourself too seriously, and the self-deprecating character he developed from it has served him well in his post-football career in TV and radio broadcasting. It also established a foundation for what he calls his biggest role: Dad.

“I think what’s most important is to share the lessons you have already learned and save them from the heartbreak and anguish they would have to go through from learning it themselves,” said Smith, who shared parenting duties with wife, Kimberly Hunt, the long-time Channel 10 KGTV evening news anchor.

Smith, who for years co-anchored the morning Scott and BR sports radio show—first on 690 AM, then 1090 AM—was home most afternoons and evenings with their daughter, Savannah. It wasn’t until Savannah, now 23, was away at college that the radio show changed to the afternoons.

Smith, who for years co-anchored the morning Scott and BR sports radio show—first on 690 AM, then 1090 AM—was home most afternoons and evenings with their daughter, Savannah. It wasn’t until Savannah, now 23, was away at college that the radio show changed to the afternoons.

“I say this all the time, no dad—no dad—got to spend as much time with their kid as I did because of our situation,” he said. “I got pretty much to be Mr. Mom and it was the greatest thing that I think I’ve ever done. Everything played out the way that I saw it playing out, that I wanted it to play out. Spending those evenings watching Kimberly on TV, and Savannah would normally lay on my chest, and we would just sit there and watch Mom. Then we would look at each other and we’d laugh. Then we would watch Mom a little while longer. That was the first two, three years.”

Over the years, Smith would help with homework, though her appreciative parents describe Savannah as a self-starter.

“I’m great with math. Second grade math, I’m cool. You sit me down with an algebra book, I might have a problem or two,” he said, another peal of laughter escaping a wide grin.

Smith also enjoyed helping Savannah with history, one of his academic loves. As a child he often pored over the books in his dad’s library, reading about the Civil War and absorbing presidential biographies.

“It was a really cool way to learn about history, just one guy at a time,” Smith said.

Decades later he can still recite the names of all the presidents in order of their election, though he needs to sneak several breaths to maintain his cadence.

Bleacher view

As Savannah got older Smith attended most of his daughter’s volleyball games and rehearsals and, as with many of his other parenting skills, he reached back to his childhood for guidance.

“I remember my dad and how he handled it,” he said. “Savannah could hear me laughing like I heard my dad. If she messed up a play I would laugh—and Kimberly would nudge me a little. That tells her that’s OK. If you can’t laugh at yourself in any situation—but most importantly when you are in front of a couple hundred people in a high school gym or a junior high gym—you are taking it way too serious. You’ve got to have a good time. If you can’t have a good time then we need to sit you down and try to drill that into you a bit.”

Smith learned how to have a good time while hanging out with the Baltimore Colts, where his dad played for 10 years, including a Super Bowl victory his last season.

“When I say I’m the luckiest guy in the world, I was the luckiest kid in the world,” he said. “Every summer I would be a regular at the Colts practices with Johnny Unitas and Mike Curtis and Bubba Smith and Billy Ray Smith and Don Shula and all the great players and coaches that the Colts had in the ’60s. I was just right there walking around… When I got out of college and made the jump to the pros, it wasn’t a big deal to me because I had been there.”

As much as he learned from his dad’s on-field prowess, the younger Smith said he appreciates the example his father set off the gridiron.

“It was family and discipline and honor,” he said. “You had to be incredibly honest. Regardless of whether you were playing in front of 70,000 people or you were just walking down the street there was a code of honor that my dad lived by that he taught me. It was something that we talked about a great deal.”

Billy Ray looks back: In Dad’s footsteps

A self-professed homebody, Billy Ray Smith said he was motivated in life by a strong respect for his own father, which led Junior to follow his dad’s footsteps to the University of Arkansas. Taking another cue from his father, Smith Jr. earned a degree in finance. After retiring from the Colts in 1971, the elder Smith became a stockbroker.

“I never thought I could do the job my dad did,” his son said. “He worked so hard as far as the stock brokerage thing. I was just glad that there was a radio station and a TV station that wanted old players to come on and talk.”

While nursing an injury prior to his own retirement from the NFL in 1992, Smith began doing scouting reports for KGTV, a gig that eventually led to sports anchoring duties. By 2001, he and his radio partner Scott Kaplan launched the Scott and BR Show. That was also the year that Smith lost his father.

“As far as being a father, I looked to him and all the examples that he set,” the sportscaster said. “The core values that I learned from my dad, I think that was the number one thing that Kimberly and I—because her parents were just like my parents—passed on to Savannah. I think that we both did a good job kind of passing on the good things from our parents to Savannah.”

Even with the strong role modeling from his dad, Smith admits he wasn’t prepared for the full scope of fatherhood—and its impact on the heart.

“I don’t really know that you have that parental, the paternal, type of love. That is something that I had no idea until it actually happened,” he said, pausing as his linebacker defenses fade. “I’m getting a little gushy now.”

The most difficult moments, Smith said, were the times that he helped his daughter process emotional pain.

“To see anybody that you love cry is the hardest part of parenting,” he said before pausing to swallow, “but if you can be funny, if you can exploit it, if you can make her feel better and stop crying, then that’s why Dad’s there. That’s why Dad and Mom are there. … Those would be the situations that I realized that it was a lesson that had to be learned and that she’d be stronger on the other side of it.”